An Australian mining company has been fined nearly A$1 million (approximately US$670,000) over the death of a 25-year-old underground mineworker—a clear example of corporate accountability that raises a pressing question for Zimbabwe: Will local mines, including small-scale operations, ever face public prosecution or meaningful financial penalties for fatal workplace incidents?

By Ryan Chigoche

In a country where over 200 mining deaths are recorded annually, and where small-scale and informal mining—often harder to regulate—accounts for the vast majority of fatalities, the question becomes even more urgent: will the arm of the law ever stretch far enough to preserve the value of life across the sector?

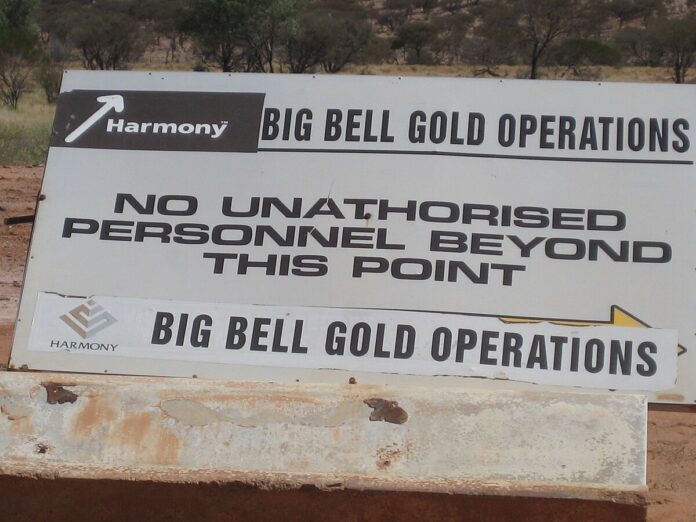

Australian gold miner Big Bell Gold was penalised over an incident that occurred in December 2020, when 25-year-old Paige Counsell was struck by a truck during a night shift at the company’s underground mine in Western Australia’s Murchison region. A Perth court this month found the company guilty of failing to provide a safe workplace and imposed a fine of A$945,000, plus an additional A$20,000 in legal costs.

Deputy Chief Magistrate Elizabeth Woods said there had been a failure of policy, process, and training, citing poor communication systems between vehicle operators and pedestrians underground. She also flagged inadequate designated safe zones and a lack of specific training as key gaps that contributed to the tragedy.

Though the company expressed remorse and has since erected a stone memorial at the mine, the most significant outcome of the case was the successful public prosecution and financial penalty.

The prosecution, brought by the Department of Mines in 2023 with support from WorkSafe WA, was a strong statement that mining safety breaches—even if not directly responsible for a fatality—would face serious legal consequences.

In Zimbabwe, such outcomes remain virtually unheard of

Despite decades of deadly accidents, few—if any—mining companies have ever been fined publicly over workplace deaths. Investigations into fatal incidents are typically conducted by the Ministry of Mines Inspectorate or the National Social Security Authority (NSSA), but these seldom translate into court proceedings or monetary penalties. Instead, compensation is often handled quietly between employers and the families of deceased workers.

According to NSSA, Zimbabwe’s mining sector is contributing an average of 200 workplace deaths annually. In 2023 alone, 237 miners lost their lives—a number that drew national attention but no corresponding criminal or financial accountability from companies.

While 2024 saw a 33% reduction in deaths, with the Chamber of Mines reporting 143 fatal accidents resulting in 186 deaths, the figures still reveal worrying trends. Small-scale and illegal operations accounted for 90% of the accidents and 87% of fatalities. Large-scale mines, although better equipped, were responsible for 10% of accidents and 13% of deaths.

And the trend continues into 2025. In the first quarter alone, 42 fatal accidents were reported in the mining sector, resulting in 53 fatalities. Three of these incidents involved large-scale mines, again underscoring the disproportionate risks in informal mining but also raising concerns about whether safety compliance is truly being enforced—even among better-resourced players.

The contrast with Australia is stark. There, the legal system holds companies to account with a clear mandate: if a worker dies and procedures are lacking, someone must answer. In Zimbabwe, even as the mining industry remains a key pillar of the economy, the loss of life rarely leads to consequences beyond the mine fence.

Until laws are enforced, prosecutions initiated, and fines issued in open court, Zimbabwe’s mining sector—particularly its small-scale and artisanal segment—will remain a zone where human life is undervalued and justice seldom delivered.

A Systemic Gap With Human Costs

The Big Bell case exemplifies what happens when a functional legal system treats a mining fatality not merely as an accident, but as a breach of duty. The resulting fine and legal process send a clear message to the industry: safety is not optional.

In Zimbabwe, the lack of consequences has allowed preventable accidents to become routine. While the numbers fluctuate year to year, the structural problem remains unchanged: enforcement is weak, accountability is rare, and justice for victims is often elusive.

Unless the legal and regulatory environment evolves to prioritise occupational safety and demand corporate responsibility, Zimbabwe’s mines will continue to see lives lost with little more than informal compensation to show for it.