State-owned enterprises have a bad reputation in Zimbabwe, and often deservedly so, with even the best usually under-capitalised, having been unable to make enough profit for replacement of the museum pieces they use for machinery, and the worst with reputations of padded payrolls, executives who seem incapable of running a tuckshop let alone anything larger, and audit reports that outline wide-scale abuse of office or corruption.

Finance and Economic Development Minister Mthuli Ncube, who in the end has to deal with dubious CEOs hanging around the corridor outside his office clutching begging bowls, could be forgiven for feeling they are a lot more bother than they are worth.

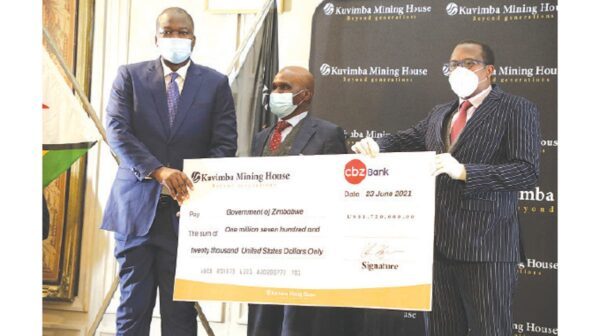

But then this week he had a different experience, being guest of honour at the first dividend announcement of the newest, Kuvimba Mining House, where US$5,2 million was distributed with 65 percent of that going to entities and funds in the public sector, around US$3,4 million in revenue that is “off budget”. He looked rather happy and who could blame him since he had got it right.

His boss, President Mnangagwa, will be pleased also. He has already shown his intense interest, presiding over mine reopening ceremonies, visiting mines, watching Zimbabweans with good jobs getting back to work and seeing in concrete form the success of the difficult and necessary reforms he has presided over.

So what is different about Kuvimba?

Kuvimba was set up late last year to take over a set of mining assets, quite a lot under judicial management, but which on careful examination appeared to be fundamentally sound, that is they had large ore bodies that could be mined profitably rather than being worked-out holes in the ground fit for little but conversion into toxic-waste repositories.

That was a crucial first point. Some State-owned enterprises are almost trying to resuscitate the ox-wagon industry, an exaggeration perhaps, but are kept going because they are there rather than because they are needed. But when you start with mines that can produce for years to come, you have something to work with.

The next point was to examine why these assets, which had all been in the pure private sector and many owned by external investors, had failed or were limping along under a court-appointed manager owing money to everyone. Digging in it was found that the owners had not been reinvesting profits in good times, and in an incredibly cyclic industry like mining that is critical, and had been milked for revenue, basically a form of asset stripping.

Inadequate management was, in many cases, unhelpful and recruiting decent managers difficult since the best people, and Zimbabwe has produced some first-class mine managers, prefer working for success stories, rather than taking orders to run something into the ground.

The topsy-turvy Zimbabwean economy with its bouts of hyperinflation, and a foreign currency policy administered by bureaucrats and diktat rather than markets, made life difficult for some of these investors and they decided not to bother. And political decisions in the declining years of the First Republic were another big turn-off.

This was not to say that all investors were turned off. Some managed rather well and saw the potential of the Zimbabwean mining industry and were willing to make the effort to ride out the storms in the expectation that we would be able to sort out the fundamentals. With the advent of the Second Republic they have justified their faith and have taken the lead in pushing forward. That example made Kuvimba possible.

The second interesting point about Kuvimba when it was set up was getting the structure and management right. For a start, private investors took 35 percent of the equity and, from what can be gathered, did this through a single entity. And those investors, like all investors, were in the operation to make money and had no doubt read the geology reports and studied the accounts very carefully before coming in with their cash.

The State’s 65 percent was not a single investment, but rather split between a number of interested parties. That provides a large block of important shareholders who are not going to let one bureaucrat make decisions. It is fairly obvious now that the Government saw its investment as a way of funding, without taxpayer assistance, a number of crucial areas, everything from raising money for venture capital for youths, starting the conversion of public service pensions to a fund rather than an annual Parliamentary vote, to starting to implement the critical deal with the expropriated farmers. And the dividend cheques still give Minister Ncube a decent sum for his capital budget.

But critically the public entities and funds that were allocated equity are reliant on Kuvimba working well. They are not going to tell professionals how to mine gold or nickel or platinum, or who to hire to do the digging, but are going to be looking over the management shoulders to make sure that the business is run properly and, critically, justifies the investments.

The next step, after securing investment, was to get the management right. Rather than “jobs for the boys”, that is well-connected former school friends, relatives or in-laws, Kuvimba went for the professionals, largely chosen by the private investors. This started with the CEO, someone who climbed the greasy pole in a major South African mining house, restructured a failing set of mines in South Africa and was seeking a new challenge.

The chairman, the recently-retired number two public servant who had the depressing experience of looking over failing State enterprises and so knew what can go wrong, was there to represent that block of public shareholders and sort of make sure that Kuvimba’s managers delivered, without telling them how to dig holes in the ground, and generally provide that oversight a proper board is supposed to give and often, in the State sector, has failed to do. With a decent board, with muscle, asking the right questions, on time, managers know what is expected and, most importantly, the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission does not have to hang around clutching handcuffs.

So we have the formula, a Second Republic formula for its first major State enterprise: a public-private partnership, decent assets, a dispersed State shareholding, a professional management and a board that has the muscle to do its job. And zero corruption.

And the results are coming in. Freda Rebecca gold mine is producing record quantities of gold, 300kg in May. That comes to around 24 of those big bars you see in pictures of Swiss bank vaults or Fort Knox. Shamva Gold Mine is out of the woods, has rehired the miners whom the judicial manager had to let go, is back in full production and has plans to tackle the next block of the ore body with an open cast mine. Its target is 400kg a month. Bindura Nickel, and ZimAlloys, are back in producing, refining and selling nickel. And the joint investment with a Russian giant for the third huge platinum mine is on course and should next year start adding to the revenue.

There has been talk about floating Kuvimba on the Zimbabwe Stock Exchange. That needs to be seriously considered. It first of all values the shares that the public and private entities hold, even if most investors want to hold on to their stakes. Secondly it allows new equity to be raised when necessary, important for a growing concern. While existing shareholders obviously are keen to retain present dividend income, and see it rise, if a business is growing properly then that is possible as well as seeing more shareholders coming in with properly-priced investment.

Thirdly a floatation would allow other Zimbabweans to invest directly. Very few people can ever own a gold mine, nickel or a platinum mine. But they can own a few hundred shares in a well-balanced group and enjoy the modest “bonus” at dividend time. The failed and simplistic indigenisation policy of the First Republic was never going to empower ordinary people, and was built around the false premise that there was a fixed block of wealth that could be divided differently. But that does not mean ordinary Zimbabweans should not be able to participate directly in the most productive sectors of the economy.

But regardless of how the future opens up, the main lesson from Kuvimba is that given the right conditions, a State-owned enterprise can be properly run, can be honestly and properly managed, can contribute to the country and the fiscus. It provides a model for others.