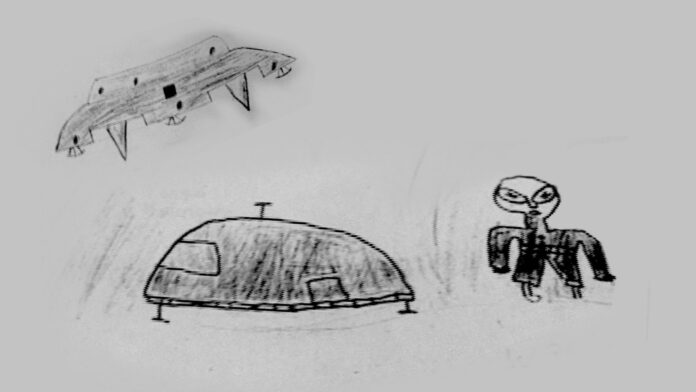

On September 16, 1994, a quiet morning at Ariel School in Ruwa, Zimbabwe, turned into one of the most perplexing and profound moments in modern history. Over sixty schoolchildren reported seeing a strange craft descend from the sky and land near the bush surrounding their school. They claimed that beings with large heads, slender bodies, and massive black eyes emerged and communicated with them, not through speech, but telepathically.

By Rudairo Mapuranga

The children, aged between six and twelve, were terrified, confused, and deeply affected. But what happened next was even more telling: instead of the world listening, it dismissed them.

Today, the Ariel School incident is often cited among the most compelling cases in UFO history. However, in Zimbabwe and much of Africa, it remains largely unacknowledged, obscured by layers of disbelief, skepticism, and colonial-era dismissal. Critics called it mass hysteria, a hoax, or childish imagination. But perhaps the truth is far more unsettling: that these children were telling the truth, and the world simply wasn’t ready to hear it, especially coming from Africa.

Why were the children not believed? Why did the narrative quickly shift toward discrediting them? And most importantly, what did the beings say? According to many of the children, the message was clear: humanity is endangering the planet through technology and environmental destruction.

Let’s pause here. This wasn’t just a UFO sighting. It was, at its heart, a warning. In the middle of a peaceful Zimbabwean schoolyard, far from Hollywood and telescopes, came a plea for environmental stewardship through the eyes of innocent children.

In a world now suffering under the weight of climate change, biodiversity collapse, water scarcity, and land degradation, that message rings louder than ever. Zimbabwe, too, stands at a crossroads. As we dig deeper into the earth to extract value through mining, especially with the rise of lithium, gold, platinum, and rare earths, we must ask:

Are we balancing development with sustainability? Or are we speeding toward the same crisis those children may have been warned about three decades ago?

Mining is essential for national development, and Zimbabwe’s Vision 2030 relies heavily on the sector to achieve a middle-income economy. Yet unregulated artisanal mining, pollution of river systems, deforestation, and failure to rehabilitate mined-out land are creating scars that may never heal. Are we listening to the earth, or only to the profit margins?

What if the alien beings weren’t just watchers of the sky, but guardians of the earth? What if the beings chose Ruwa not by accident, but because Africa, with its relatively untouched lands and spiritual heritage, still has a chance to choose a different path?

Zimbabwe’s mining sector is growing rapidly. Lithium, called “white gold,” is fueling a green energy transition globally. Zimbabwe is home to massive lithium deposits in Bikita, Goromonzi, and Kamativi. But while the demand for lithium grows, so does the pressure on our environment. Tailings dams, water use conflicts, relocation of communities, and ESG obligations are now central challenges. Yet amid these technical and economic realities, we seldom return to the soul of the matter: what is our relationship with the land?

The Ariel School incident offers us an unusual lens—spiritual, moral, and ecological. It reminds us that our development must have direction, not just speed. Just as the children saw beings who warned about the destruction of Earth, Zimbabwe today sees the consequences of extractive industries that are not always mindful of the future.

Ruwa, at that moment, became a stage not just for an unexplained encounter, but for a conversation about truth, power, and planet. The children’s testimony was powerful, unified, and remarkably consistent—even decades later. Most of them, now adults scattered around the world, still stand by what they saw.

Their voices were pure. They had no incentive to lie. They weren’t seeking YouTube views or TV deals. They were traumatised. Some were mocked. Others were silenced by their families. But their truth never changed. That matters.

As we move toward more advanced mining practices, there is a push for environmental audits, community beneficiation, and the inclusion of local voices. Could we learn from the Ariel School children, who spoke a truth that was inconvenient but sincere? Could we apply the same principle listening to communities around Hwange, Mutoko, Marange, and Penhalonga, where mining operations often clash with traditional land use, water rights, and cultural values?

This story is not only Zimbabwean. It is planetary. But we, as Zimbabweans, hold the key to reshaping how the world sees it, not as a fringe incident, but as a profound message rooted in African soil.

Let us imagine a scenario: a young Zimbabwean geologist sits at a lithium mine near Arcadia, reading about the Ariel School case for the first time. Instead of dismissing it, he reflects: “If children once carried a message from beyond, maybe we are being asked to carry one now—from the Earth itself.”

That’s the power of the Ariel legacy. It invites introspection. It offers an opportunity to build a mining sector that doesn’t just extract—but regenerates. One that doesn’t just enrich the nation—but preserves its natural and spiritual wealth.

Imagine if every Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process began with a reading of the Ariel testimony. Imagine if miners, engineers, policymakers, and community leaders saw themselves not just as extractors, but as stewards—guardians of the earth, just as those children were briefly guardians of a cosmic message.

The warning given in 1994 could be the compass we need in 2025. Climate change is no longer a theory. Droughts, cyclones, and erratic rainfall patterns have reshaped farming. Rivers are running dry. Even artisanal miners know this—digging deeper for less, watching the rains delay year after year. What if we listened not just to machines and markets, but to memory? What if we remembered what was said that morning in Ruwa?

In schools, we teach science, geography, and economics. But the Ariel story teaches something deeper: the interconnectedness of all things—the land, the sky, the water, and the unseen forces that may still walk beside us.

This is not about superstition or folklore. It is about respecting knowledge, whether it comes in textbooks, satellite data, or the silent testimony of a child staring wide-eyed at the sky.

In 1994, the stars came to Ruwa. The world turned away. But today, we can turn back and listen—not only to what those children said, but to what the land, the air, and the spirit of our nation are still trying to say.

We were warned. Are we ready to act?

.png)