Zimbabwe among other African countries has its economic mainstay in agriculture and mining. The existence of mines has created a mining community of citizens living on mine property and around the mine areas.

Edmond Mkaratigwa (MBA in Energy and Sustainability and Chairperson of the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Mines and Mining Development)

Albert Maipisi (Phd in Disaster Management).

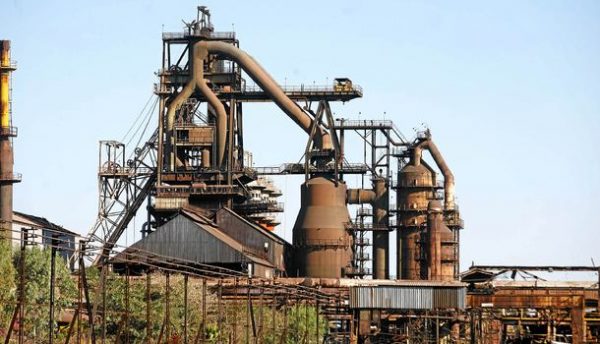

These mines have a life span that ends, suspend operations for long periods and or cede mining rights to new investors that may come in with completely new approaches. That is when sustainability issues arise and in particular when the mining community fails to earn meaningful living post mine operations. Government approaches have focussed more on environmental sustainability while mining companies have focused on corporate sustainability (CS) that gives birth to corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. Observations were however made on disused mines in Zimbabwe and reflect weaknesses in government and mining companies’ sustainability approaches post-mining.

Where mines exist, physical infrastructure and facilities development follows. Key infrastructures include tailings dams, electricity supply hardware, shops, social halls, and buildings as well as workers’ houses. On tailings dams, they are naturally supposed to be fenced and the fences among other infrastructure normally exist during the mine’s existence and are vandalised a few years later. Former mineworkers living in mine houses and the surrounding communities, therefore, are exposed to different hazards and vulnerabilities therefrom. In some disused mines, the former mineworkers have remained in mine houses anticipating a re-investment into the mine someday, without sustainable livelihoods. Where that exists, those from such communities have been observed fishing in the unmaintained tailings dams. That endangers human life to both crocodiles and pursuant health risks associated with swallowing residual mineral processing chemicals for example through eating the fish.

Former workers of the disused mines have been residing in disused mines’ residences because of different reasons. Some remain there as they await the payment of outstanding salaries, others anticipate the mining operations will resume sooner while some have nowhere to go in terms of alternative accommodation. Hence those who remain at those areas are faced with other challenges. They include failure to access essential services such as electricity, water, and viable shops than those that overprice. Electricity infrastructure gets vandalised affecting electricity supply and eventually, water supply that is mostly attached to electricity availability. Rates formally paid to responsible authorities for housing and electricity also usually remain un-serviced. That threatens further those former workers residing in the houses although that brings in the property rights issue which is not the current subject of this discussion. Those factors, therefore, further increase vulnerabilities of the mineworkers or community post-mining.

In general terms, human rights are being violated post-mine life as much as the focus has been on the day the company is still in existence. Disused mines have also been reopened in some cases and former workers have not been considered in the new takeover deals yet they might have been promised to wait for the new investor. In one case, for example, a woman was 55 years old when the company closed and waited for an anticipated mining company reopening for a further 25 years. She did not get any terminal benefits nor pension from the former employer or investor and did not own a house. Surely at 75, that woman is not able to take another job even if the company would re-open. Those families living on disused mines normally have their children that then grow under very difficult economic circumstances. They are unable to access good social services such as education and health facilities with ramifications that even where the company can reopen, those children would take up menial jobs. Some will be exposed to delinquency. Where the mine is re-opened, most times the workers are not involved in takeover negotiations to the extent that they will live in uncertainty regarding their future with the investors.

That having been said, the main question is what is the real problem and the possible remedies? The first problem lies in the monitoring and sustainability management mechanism gap on the part of the company and the responsible government authority such as the Department of Wildlife and that of the Environment relative to tailings dams post-mine life. The second gap exists in weaker employee benefits insurance and hedging in the wake of inflation. The third aspect is a lack of participation or representation of the mineworkers where company ownership is being changed although miners’ property rights are strictly observed. The fourth gap debatably lies in the nature of the CSR that is more inclined to corporate sustainability as opposed to sustainability that outlives the company life.

In order to deal with some of these challenges, government should strengthen synergy for monitoring and sustainability management between mining companies and the responsible government authorities to ensure sustainable management of the environment and infrastructure post-mine life. On the other hand, the government can motivate quality and responsible investment initiatives that form the package of the investment arrangement from the onset. On weaker employee benefits insurance and hedging in the wake of inflation, whereas NSSA exists, companies should develop diverse mechanisms that can guarantee the preservation of value to cover for the post-mine life obligations. Further, government’s economic reform efforts must be wholesome and consistent. Finally, mining companies should rethink and redefine CSR in order to foster long term responsibility and sustainability of people, planet, and profits. One way is migration from CSR to CSI as is already trending in other countries.

Published ideas are entirely views of the two authors as academics and cannot be attributed to their positions.