Once again we have had meetings involving the mining industry, and one again we have discussion on the need to add value and to process our minerals before we export them, shipping out bars of metal rather than concentrates or ores or even vague alloys that do not have really precise percentages.

To a very large extent this is where the big money and the profits are, so what is the hold up and what is needed and what can be done.

For a start it has become obvious that Government action, such as bans on exports of unprocessed minerals, or tax surcharges on semi-processed metals, are not really effective. Making things difficult or impossible for investors, or cutting their profits with higher taxes, is not going to enhance our investment drive and could undo a lot of the work that has been done in the last two years to get Zimbabwe open for business.

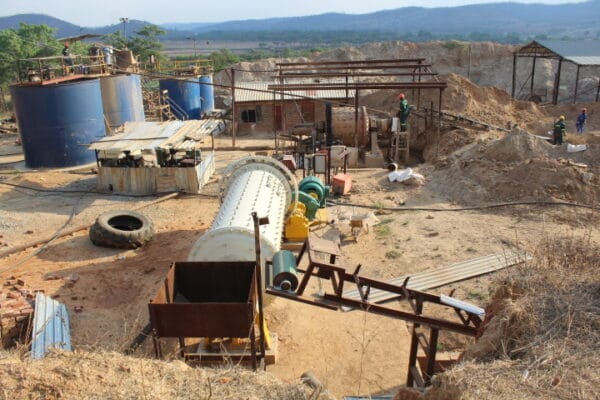

Beneficiation, to use the ugly vogue word, does require more investment, not less, and so we have to be open for investment and have to start thinking how we can make investment in the next step more attractive.

There are some major problems. The biggest is probably having enough demand for a processing plant to make the new investment profitable. As with so much volumes matter and there must be a critical mass that would make a decent refinery profitable for the owners and investors.

So the drive to open new mines is important, not just for itself but also to create those volumes that are needed.

Quite a lot depends on the mineral. When it comes to iron ore, for example, there is no way anyone can make money exporting such a high bulk and low value product from Zimbabwe. Countries that do make money from iron ore exports have rich deposits on or near the surface and very close to a port deep enough and big enough for modern bulk carriers to berth. So northwest Australia makes money from iron ore exports.

However, because all the raw materials for steel production are in Zimbabwe, plus the metals that are needed to alloy with iron in complex steels, such as the specialist stainless steels, investment in the iron business means investment in modern steel mills, and two Chinese investors have now committed themselves to this.

It took an investor-friendly policy to get that investment in the first place, and we know this because the first investor backtracked quite a bit until the Second Republic made the legal and policy changes to get the work back on course, and the second investor was not really interested until the necessary legal and policy changes were in place to start with.

But once we made it a lot easier to set up business the pure economics of the investment came into play and when those Chinese investors did their calculations they worked out that they could make money after sinking in a lot of investment capital and so are now proceeding.

Platinum mining is a growing investment. But at the moment the economics mean that the exports are in the form of concentrates that undergo the final refining process in South Africa. Part of this is because there are the required refineries in South Africa that can split out the range of platinum-group metals that are in the concentrates, and partly because the initial platinum miners were already using those refineries for their South African production and there was enough spare capacity to handle the extra from their Zimbabwean mines.

By the time you have processed the Zimbabwean ore down to concentrates the transport costs are not that great, especially when the lorry only has to go a few hundred kilometres on a good road, so it is easy to see how the economics militate against a huge investment into a Zimbabwean refinery.

But as more mines open, and another giant mine, this time with Russian investors, is already in the process of being dug and opened, the volumes start rising. It is likely that more mines will open and equally likely that these mines will have other investors, spreading ownership of the platinum industry.

So any refinery in Zimbabwe will have the volumes that justify investment, but probably only if everyone has a share and everyone uses it. Ideally we are talking about a single refining company under joint ownership or with a refining cost structure in place that makes it worthwhile to use it. Since most mining companies are likely to be reluctant to give any special treatment to their competitors, the joint-ownership option appears to be the more obvious route.

When we come to base metals, such as chrome and nickel, we have additional complexities. A chunk of this mining is done by small-scale miners and it is this group that apply pressure to allow export of ores. A major mining company is more likely to want to export ingots of at least semi-processed metal, such as ferrochrome, with the percentages of each metal in each batch of ingots carefully worked out and stamped on the bar and in the documentation.

But once again if this is to be norm then ways have to be worked out to ensure that all ores delivered are bought at a fair price, fair to miner and refiner, or if the miners are to retain ownership of the metals and arrange their own exports, a double-fair pricing formula for refining charges needs to be agreed.

The colonial authorities eventually banned ore exports, and not only did the economics then work out with that ban, but no one in Ian Smith’s office really cared one iota about small-scale miners. Generally they were banned as well. Things are now different, both in economics and in the mining field.

The economic mess in Zimbabwe in the latter decades of the First Republic did not help, making investment difficult and making even the maintenance of refineries problematical. That has been fixed, but we still need to work out how the equivalent of outgrowers can work. The sugar industry solved the problem, so there are examples in place.

Even when we come to something like gold, where refining is relatively simple and where all gold by law has to go through a single buyer, there is still a problem at the extreme end of the process. Fidelity is not yet accepted as a producer and certifier of bars of gold that can be sold as pure bullion. The standards are there; it is just a final licensing arrangement that is needed.

For some products, such as lithium, we will never export the actual metal. Lithium has to be exported as a salt, and if we ever managed to find large exploitable reserves of uranium that would be in the same category. But as lithium starts entering out exports again we are going to have to start working out how we can do the final processing into the tradable commodity in Zimbabwe, or at least set the investment climate so that producers will want to do the final processing in Zimbabwe.

So the talk is not being wasted. But we need to move away from generalisations to the actual detailed specifics of what mineral processors and refiners will need. A good investment climate, and the required volumes of minerals to be processed, are just the start.

There will be things like guaranteed power supplies, at a cost that competes with South Africa so relying on imports from South Africa is not really helpful.

There is the need to build the required level and base of skilled manpower quickly, since expatriate workers are always high cost. One reason why mining can boom is that there are Zimbabwean mining engineers and mineworkers now who can do all that primary production, but when you move into the next stage the need for trained and experienced staff moves onto the agenda.

The development to meet these additional requirements have been included into Government planning, that is why the National Development Strategy involves so many aspects, because everything has to be included and be ready when needed. But planning works best when everything is listed and we need, as we move towards high-level beneficiation, that the potential investors have indeed listed all their requirements.